Filters

Host (768769)

Bovine (1090)Canine (20)Cat (408)Chicken (1657)Cod (2)Cow (333)Crab (15)Dog (524)Dolphin (2)Duck (13)E Coli (239129)Equine (7)Feline (1864)Ferret (306)Fish (125)Frog (55)Goat (36948)Guinea Pig (752)Hamster (1376)Horse (903)Insect (2053)Mammalian (512)Mice (6)Monkey (601)Mouse (96266)Pig (197)Porcine (70)Rabbit (358746)Rat (11724)Ray (55)Salamander (4)Salmon (15)Shark (3)Sheep (4265)Snake (4)Swine (301)Turkey (57)Whale (3)Yeast (5336)Zebrafish (3022)Isotype (156931)

IgA (13628)IgA1 (941)IgA2 (318)IgD (1949)IgE (5594)IgG (87426)IgG1 (16736)IgG2 (1332)IgG3 (2719)IgG4 (1689)IgM (22047)IgY (2552)Label (239355)

AF488 (2465)AF594 (662)AF647 (2324)ALEXA (11546)ALEXA FLUOR 350 (255)ALEXA FLUOR 405 (260)ALEXA FLUOR 488 (672)ALEXA FLUOR 532 (260)ALEXA FLUOR 555 (274)ALEXA FLUOR 568 (253)ALEXA FLUOR 594 (299)ALEXA FLUOR 633 (262)ALEXA FLUOR 647 (607)ALEXA FLUOR 660 (252)ALEXA FLUOR 680 (422)ALEXA FLUOR 700 (2)ALEXA FLUOR 750 (414)ALEXA FLUOR 790 (215)Alkaline Phosphatase (825)Allophycocyanin (32)ALP (387)AMCA (80)AP (1160)APC (15217)APC C750 (13)Apc Cy7 (1248)ATTO 390 (3)ATTO 488 (6)ATTO 550 (1)ATTO 594 (5)ATTO 647N (4)AVI (53)Beads (225)Beta Gal (2)BgG (1)BIMA (6)Biotin (27821)Biotinylated (1810)Blue (708)BSA (878)BTG (46)C Terminal (688)CF Blue (19)Colloidal (22)Conjugated (29246)Cy (163)Cy3 (390)Cy5 (2041)Cy5 5 (2469)Cy5 PE (1)Cy7 (3638)Dual (170)DY549 (3)DY649 (3)Dye (1)DyLight (1430)DyLight 405 (7)DyLight 488 (216)DyLight 549 (17)DyLight 594 (84)DyLight 649 (3)DyLight 650 (35)DyLight 680 (17)DyLight 800 (21)Fam (5)Fc Tag (8)FITC (30172)Flag (208)Fluorescent (146)GFP (563)GFP Tag (164)Glucose Oxidase (59)Gold (511)Green (580)GST (711)GST Tag (315)HA Tag (430)His (619)His Tag (492)Horseradish (550)HRP (12964)HSA (249)iFluor (16571)Isoform b (31)KLH (88)Luciferase (105)Magnetic (254)MBP (338)MBP Tag (87)Myc Tag (398)OC 515 (1)Orange (78)OVA (104)Pacific Blue (213)Particle (64)PE (33571)PerCP (8438)Peroxidase (1380)POD (11)Poly Hrp (92)Poly Hrp40 (13)Poly Hrp80 (3)Puro (32)Red (2440)RFP Tag (63)Rhodamine (607)RPE (910)S Tag (194)SCF (184)SPRD (351)Streptavidin (55)SureLight (77)T7 Tag (97)Tag (4710)Texas (1249)Texas Red (1231)Triple (10)TRITC (1401)TRX tag (87)Unconjugated (2110)Unlabeled (218)Yellow (84)Pathogen (489925)

Adenovirus (8665)AIV (315)Bordetella (25035)Borrelia (18281)Candida (17817)Chikungunya (638)Chlamydia (17650)CMV (121394)Coronavirus (5948)Coxsackie (854)Dengue (2868)EBV (1510)Echovirus (215)Enterovirus (677)Hantavirus (254)HAV (905)HBV (2095)HHV (873)HIV (7865)hMPV (300)HSV (2356)HTLV (634)Influenza (22132)Isolate (1208)KSHV (396)Lentivirus (3755)Lineage (3025)Lysate (127759)Marek (93)Measles (1163)Parainfluenza (1681)Poliovirus (3030)Poxvirus (74)Rabies (1519)Reovirus (527)Retrovirus (1069)Rhinovirus (507)Rotavirus (5346)RSV (1781)Rubella (1070)SIV (277)Strain (68102)Vaccinia (7233)VZV (666)WNV (363)Species (2982410)

Alligator (10)Bovine (159564)Canine (120648)Cat (13087)Chicken (113785)Cod (1)Cow (2030)Dog (12746)Dolphin (21)Duck (9567)Equine (2004)Feline (996)Ferret (259)Fish (12797)Frog (1)Goat (90471)Guinea Pig (87888)Hamster (36959)Horse (41226)Human (955212)Insect (653)Lemur (119)Lizard (24)Monkey (110914)Mouse (470804)Pig (26204)Porcine (131703)Rabbit (127621)Rat (347847)Ray (442)Salmon (348)Seal (8)Shark (29)Sheep (104996)Snake (12)Swine (511)Toad (4)Turkey (244)Turtle (75)Whale (45)Zebrafish (535)Technique (5601007)

Activation (170393)Activity (10733)Affinity (44710)Agarose (2604)Aggregation (199)Antigen (135358)Apoptosis (27447)Array (2022)Blocking (71767)Blood (9451)Blot (10966)ChiP (815)Chromatin (6286)Colorimetric (9913)Control (82142)Culture (3226)Cytometry (5481)Depletion (54)DNA (172449)Dot (233)EIA (1039)Electron (6275)Electrophoresis (254)Elispot (1294)Enzymes (52671)Exosome (4280)Extract (1090)Fab (2236)FACS (43)FC (80947)Flow (6666)Fluorometric (1407)Formalin (97)Frozen (2678)Functional (708)Gel (2484)HTS (136)IF (12906)IHC (16566)Immunoassay (1589)Immunofluorescence (4119)Immunohistochemistry (72)Immunoprecipitation (68)intracellular (5602)IP (2840)iPSC (259)Isotype (8791)Lateral (1585)Lenti (319416)Light (37250)Microarray (47)MicroRNA (4834)Microscopy (52)miRNA (88044)Monoclonal (516119)Multi (3844)Multiplex (302)Negative (4261)PAGE (2520)Panel (1520)Paraffin (2587)PBS (20270)PCR (9)Peptide (276160)PerCP (13759)Polyclonal (2763048)Positive (6335)Precipitation (61)Premix (130)Primers (3467)Probe (2627)Profile (229)Pure (7808)Purification (15)Purified (78469)Real Time (3042)Resin (2955)Reverse (2435)RIA (460)RNAi (17)Rox (1022)RT PCR (6608)Sample (2667)SDS (1527)Section (2895)Separation (86)Sequencing (122)Shift (22)siRNA (319447)Standard (42483)Sterile (10170)Strip (1863)Taq (2)Tip (1176)Tissue (42812)Tube (3306)Vitro (3577)Vivo (981)WB (2515)Western Blot (10683)Tissue (2021617)

Adenocarcinoma (1075)Adipose (3459)Adrenal (657)Adult (4883)Amniotic (65)Animal (2447)Aorta (436)Appendix (89)Array (2022)Ascites (4377)Bile Duct (20)Bladder (1672)Blood (9451)Bone (27330)Brain (31189)Breast (10917)Calvaria (28)Carcinoma (13493)cDNA (58547)Cell (413813)Cellular (9357)Cerebellum (700)Cervix (232)Child (1)Choroid (19)Colon (3911)Connective (3601)Contaminant (3)Control (82142)Cord (661)Corpus (148)Cortex (698)Dendritic (1849)Diseased (265)Donor (3069)Duct (861)Duodenum (643)Embryo (425)Embryonic (4583)Endometrium (463)Endothelium (1424)Epidermis (166)Epithelium (4221)Esophagus (716)Exosome (4280)Eye (2034)Female (793)Frozen (2678)Gallbladder (155)Genital (5)Gland (3436)Granulocyte (8981)Heart (6850)Hela (413)Hippocampus (325)Histiocytic (74)Ileum (201)Insect (4880)Intestine (1944)Isolate (1208)Jejunum (175)Kidney (8075)Langerhans (283)Leukemia (21541)Liver (17340)Lobe (835)Lung (6064)Lymph (1208)Lymphatic (639)lymphocyte (22572)Lymphoma (12782)Lysate (127759)Lysosome (2813)Macrophage (31794)Male (1935)Malignant (1465)Mammary (1985)Mantle (1042)Marrow (2210)Mastocytoma (3)Matched (11710)Medulla (156)Melanoma (15522)Membrane (105772)Metastatic (3574)Mitochondrial (160319)Muscle (37423)Myeloma (752)Myocardium (11)Nerve (6398)Neuronal (17028)Node (1206)Normal (9492)Omentum (10)Ovarian (2509)Ovary (1172)Pair (47185)Pancreas (2843)Panel (1520)Penis (64)Peripheral (1912)Pharynx (122)Pituitary (5411)Placenta (4038)Prostate (9423)Proximal (318)Rectum (316)Region (202210)Retina (956)Salivary (3119)Sarcoma (6946)Section (2895)Serum (25168)Set (167654)Skeletal (13632)Skin (1879)Smooth (7577)Spinal (424)Spleen (2292)Stem (8892)Stomach (925)Stroma (49)Subcutaneous (47)Testis (15393)Thalamus (127)Thoracic (60)Throat (40)Thymus (2990)Thyroid (14121)Tongue (140)Total (10135)Trachea (227)Transformed (175)Tubule (48)Tumor (76921)Umbilical (208)Ureter (73)Urinary (2466)Uterine (303)Uterus (414)Contamination in Cell Culture: Detection, Prevention, and Elimination

Contamination in cell culture can compromise results and derail entire experiments. In this comprehensive guide, explore the most common types of contamination including mycoplasma, bacteria, fungi, and cross-contamination and learn how to detect, prevent, and eliminate them using proven lab practices. Ideal for researchers, lab technicians, and cell biologists aiming to maintain clean, reliable cultures and ensure experimental reproducibility.

Genprice

Scientific Publications

Contamination in Cell Culture: Detection, Prevention, and Elimination

Types of Contaminants in Cell Culture

1. Bacterial Contamination

- Rapid-growing, often visible within 24–48 hours

- Causes turbidity, pH changes (medium turns yellow), and cell death

- Common sources: non-sterile reagents, poor aseptic technique, airborne exposure

2. Fungal and Yeast Contamination

- Slower onset, visible as floating clumps or filaments

- Fungi often grow as mycelial mats; yeast appears as budding round cells

- Thrive in humid incubators and contaminated water trays

3. Mycoplasma Contamination

- Invisible to the naked eye and standard microscopy

- Alters DNA replication, metabolism, and gene expression

- Found in up to 15–35% of global cell cultures according to studies

- Requires PCR, DNA staining, or ELISA for detection

4. Viral Contamination

- Rare but dangerous in cell lines used for vaccine production or gene therapy

- May originate from contaminated serum or infected primary cells

5. Cross-Contamination Between Cell Lines

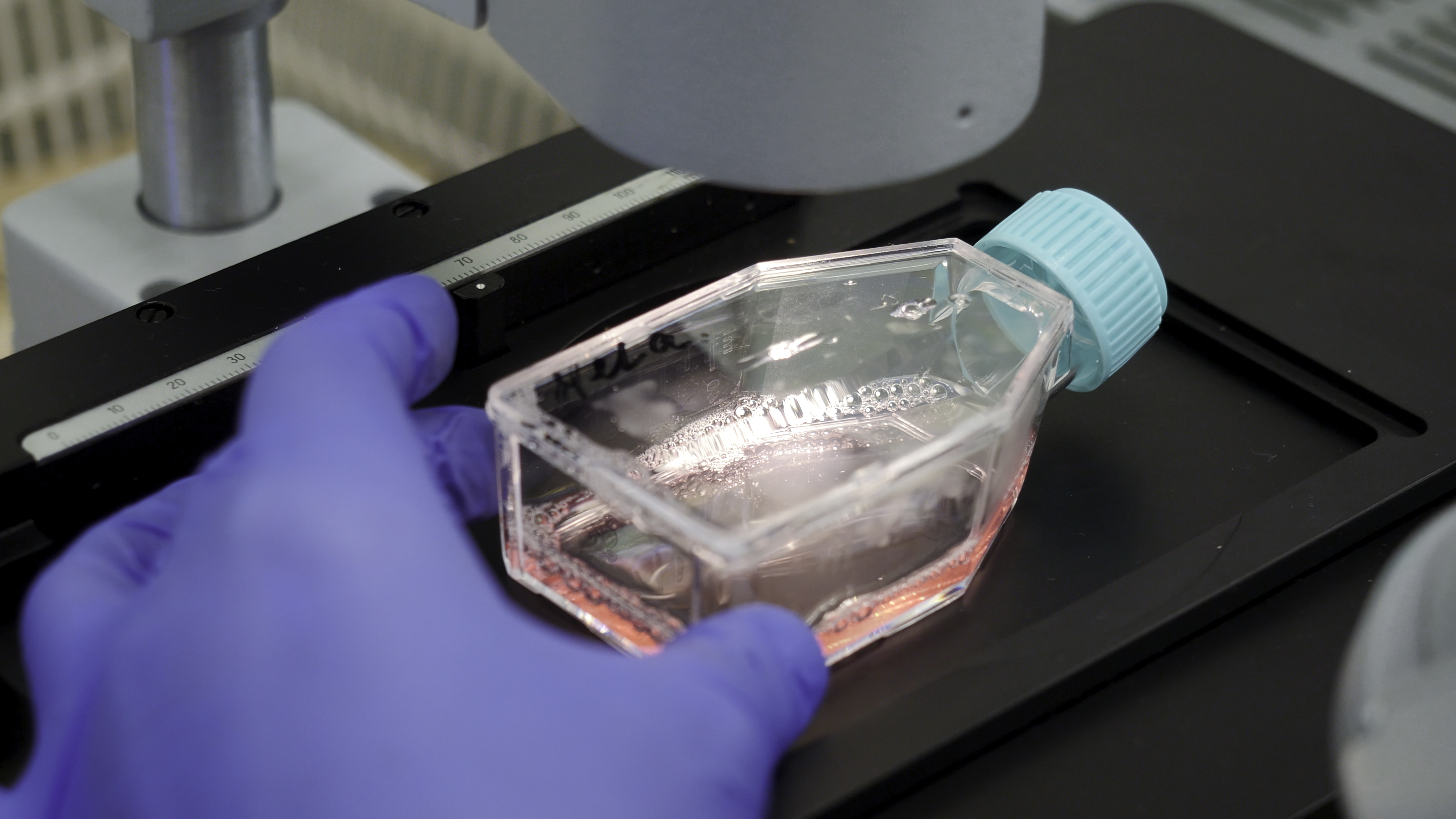

- Misidentified cell lines (e.g., HeLa overgrowth)

- Results in invalid data due to mixed genetic backgrounds

Detection Methods for Cell Culture Contamination

Common Signs of Contamination

- Sudden pH changes (yellow or purple medium)

- Cloudy media or floating debris

- Unusual cell morphology

- Reduced growth rate

- Cell detachment or clumping

- Microscopic black dots or filaments

Prevention Strategies: Best Lab Practices

1. Aseptic Technique

- Always work in a certified biosafety cabinet (Class II BSC)

- Flame pipettes or use sterile, disposable tips

- Wipe surfaces and gloves with 70% ethanol before handling cell

2. Use Antibiotic-Free Culture Whenever Possible

- Antibiotics can mask low-level contamination

- Routine use can cause resistant strains

- Ideal for early detection of contamination through observation

3. Quarantine and Test All New Cell Lines

- Always quarantine new cultures and screen for mycoplasma before use

- Keep a log of cell line origin, passage number, and test results

4. Maintain and Clean Incubators Regularly

- Clean water trays with antifungal agents (e.g., copper sulfate)

- Monthly decontamination with hydrogen peroxide or chlorine dioxide

5. Label and Track All Cell Lines and Reagents

- Use proper cell line authentication (STR profiling)

- Avoid reagent sharing between contaminated and clean lines

How to Eliminate Contamination

Bacterial or Fungal

- Discard contaminated culture immediately

- Clean all surfaces with 10% bleach followed by 70% ethanol

- Autoclave reusable materials

Mycoplasma

- Use anti-mycoplasma reagents like Plasmocin or BM-Cyclin

- Treat for 1–2 weeks, then confirm eradication via PCR

- Retreat or discard if contamination persists

Cross-contamination

- Discard mixed cultures unless genetically valuable

- Re-authenticate with short tandem repeat (STR) analysis

Economic and Scientific Cost of Contamination

- Lost cell stocks and experimental data

- Delayed publications and funding deadlines

- Risk of publishing incorrect results

- Contaminated lines may still grow and appear normal — leading to false confidence

Conclusion: Routine Vigilance is Non-Negotiable

Contamination in cell culture is not just an inconvenience it’s a major scientific risk. The best approach is a proactive one: routine monitoring, aseptic practices, and authentication of every cell line used. With regular testing and proper lab protocols, researchers can safeguard their work, ensure data accuracy, and maintain long-term culture health.